Examining The Cinematography of Jaws for the 50th Anniversary

When I saw showings popping up for the Jaws (1975) 50th anniversary, I knew I had to see it. My sister and one of my nieces happened to be free so I was even more excited to share it with the next generation. For me seeing Jaws felt like a rite of passage because it was one of the first horror films I saw.

I remember being too scared to even go into the pool afterwards!

Seeing my niece’s reaction was almost as fun as seeing the movie itself. I was scared that, as an early twenty-year-old Gen Zer who loves her phone, she wouldn’t like the slower pacing, but I was completely wrong. She jumped during the opening scene, she gasped during the beach attack, and by the end she was utterly hooked. The death of Quint also left her heartbroken (spoiler alert, but if you don’t know what happens in a 50-year-old movie, that’s totally on you).

What surprised me the most though, is how much she enjoyed the cinematography, specifically how she said she felt during the interior boat scene and the close-up shots. The score was an obvious winner, but the cinematography... that seemed to be the real star of the film.

Cinematography As A Tool Of Suspense

There is no doubt that Steven Spielberg is a phenomenal director, with movies like E.T., Jurassic Park, Indiana Jones, and Schindler’s List just a few notable mentions. One could argue that Jaws was his first major success. The reason for that is how expertly the film uses cinematography to build dread.

In fact, the camera itself often takes the role of the shark, a creature we do not see until well into the film. The shark’s-eye perspective takes us deep within the water, gliding low and deliberate, as if stalking the swimmers above, notably highlighted by the sun peeking through. The shots become more unsettling because we don’t see the shark, meaning we are both the predator and disconnected in a cold, distant way as well. This in turn amplifies the fear.

That is not to say we only see the shark’s perspective. Jaws also offers a close-up view of Chief Brody, giving us the human perspective, but because those shots are often exaggerated quick zooms or tight close-ups, his fears and anxieties become our own.

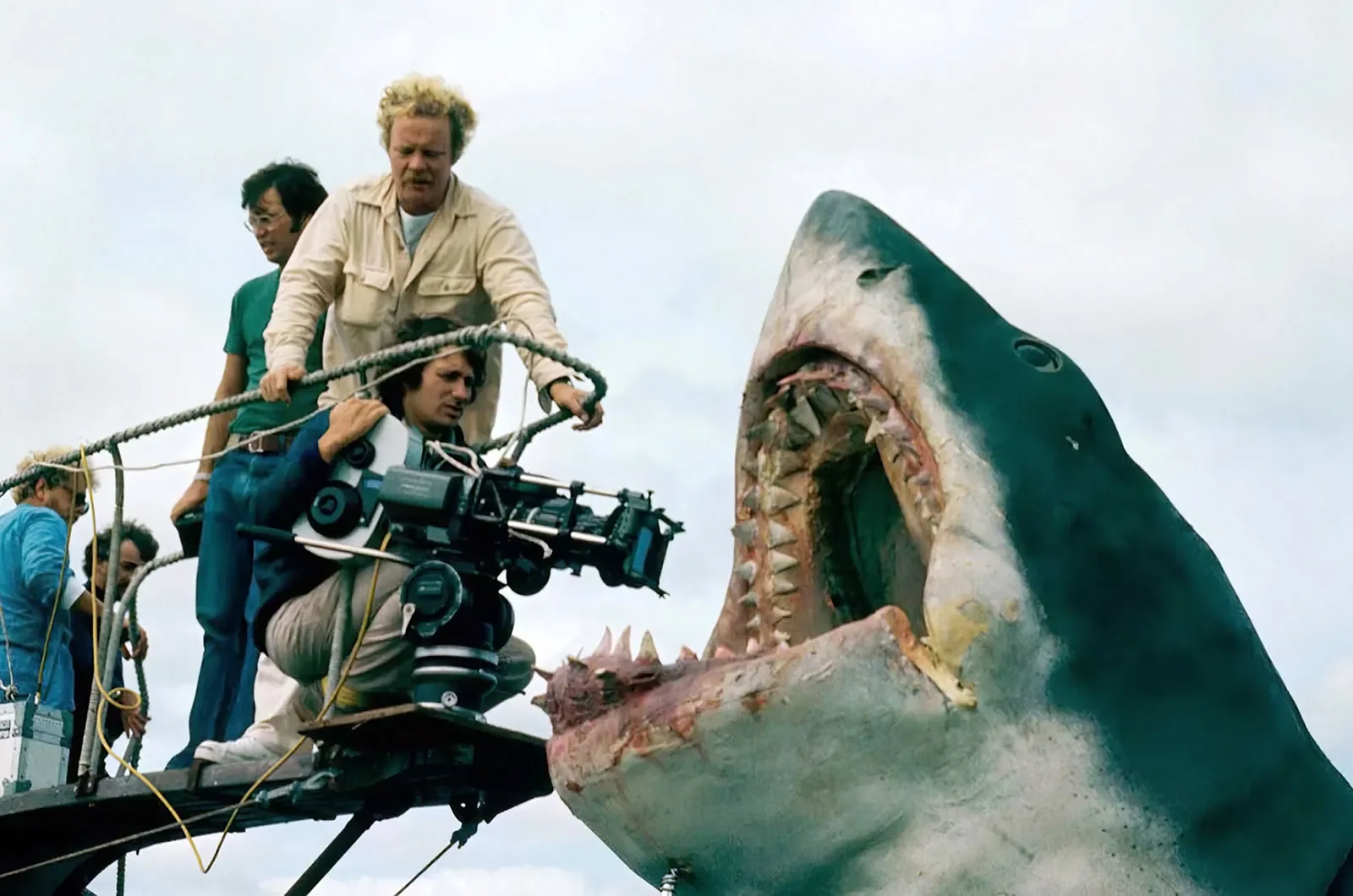

All of this works well, because while the shark is a great practical effect, it is still obviously not a real shark. Thus, the clever framing, sound design, and of course, those reaction shots, take the weight off the shark and use ambience to better carry the fear.

And it works well.

Mise en Scène in Horror

When I saw Jaws on the big screen (the first time I watched it in a theatre), I was struck by how often Spielberg chose to be selective about what we saw, how much we saw, and when we saw it. Essentially, a great deal was left to our imagination.

This felt like a classic mise en scène, which is the term in reference to the arrangement of visual elements used to create meaning. In other words, how Spielberg chose to use his props.

For example, we can see three distinct arrangements in some of the more specific deaths:

Chrissie’s Death

The opening of the movie is iconic, despite it being restrained. However, while there are probably plenty of film think pieces on this shot, especially the dun-dun, dun-dun, etc. I talked a bit about audio in my Smile 2 piece, and while there is room for that here, I think the audio work on the film is well known.

Besides, what strikes me more is how her body is shown.

It’s gory, of course, but not more than it needs to be. We see the top of her head, an arm poking up through the sand. Later the arm being examined is the last part of her we see. It is meaty, gory, but the duality of her feminine hand and the gore work as good framing mechanisms for the entire film. Spielberg exists in a space where the gore is woven so naturally it no longer feels overtly graphic or visceral.

Alex Kintner’s Death

Later in the movie a child death occurs, which should take many viewers out of the film by its nature, but it is instead framed in a long shot. We see chaos on the beach, a burst of red water, and then a strange quiet stillness. The ocean is calm and finally the camera lingers on the shredded raft and bloody clothes.

The lack of gore, and showing the aftermath, such as Ms. Kintner in mourning clothes, is far more impactful than showing us the full attack.

Quint’s Death

By contrast, Quint’s death is visceral. After so much restraint, Spielberg finally gives us a direct confrontation between man and shark. It’s messy, brutal, and up close. My niece had her hand over her mouth in shock at this one because it was so unexpected. While some might find it comical, perhaps by today’s standards, I still feel it works because of all the previous buildup.

Those previous death scenes used so much restraint that they primed the audience for this perfect moment of chaos. Quint, after all, is the one you expect to survive.

Composition and Framing of Jaws

The cinematography also does well to build tension through the composition and framing of the film overall. In my opinion, some of the most notable are:

Horizon line: The endless ocean is a constant backdrop, framing the various shots of swimmers. The smallness of these figures against the vastness of the water creates unease but also underlines the idea that we are just simple vulnerable humans that follow the rules of nature.

Foreground versus background: One of the most famous sequences features Brody watching the water while beachgoers pass in front of him, blocking his line of sight. The tension builds with every passing figure, forcing us to share his frustration and anxiety.

The dolly zoom: One of the most iconic shots in the film occurs when a vertigo effect shows Brody’s realization that a shark attack is happening. It works by simultaneously pulling the camera back while zooming in. It is a very specific trick, known as the dolly zoom, that stretches the background while we hone in on Brody’s horrified face. It works to mirror his inner panic, elevating the fear in the audience.

Why Jaws Still Works 50 Years Later

It is simply impossible to talk about the 50th anniversary of Jaws without acknowledging its place in film history. In fact, it is regarded as the first modern summer blockbuster and Jaws on the Water screenings (where you literally see Jaws in a body of water) still show up almost every summer.

Rewatching the anniversary showing just reinforced how fresh the movie still feels and how my niece probably reacted the same way my sister and I did, and my parents did when they first saw the movie.

It’s an experience that transcends generations because of the film work, which allows us to not only fear going into the water, but to use our own imaginations as the basis of that fear.

Frequently Asked Questions About Jaws and Its Cinematography

-

Released in June 1975, Jaws became a cultural phenomenon by combining wide distribution, national TV marketing, and massive box office success. Its mix of suspense, spectacle, and broad appeal set the standard for what we now call a “summer blockbuster.”

-

Spielberg and cinematographer Bill Butler relied on creative camera work to build suspense. The most famous examples include shark’s-eye perspective shots, extreme close-ups of Chief Brody, and the dolly zoom effect during the beach attack. These choices created tension without overusing the mechanical shark.

-

The mechanical shark often malfunctioned, forcing Spielberg to hide it for much of the film. This accident turned into a strength, but the decision to suggest rather than show the shark made the movie scarier and let the cinematography and sound design carry the fear.

-

Most of the movie was shot on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. Spielberg chose the location for its shallow ocean floor, which allowed cameras and equipment to capture shots that looked like open sea while still being safe for filming.

-

The cinematography was led by Bill Butler, who worked closely with Spielberg to craft the film’s visual language. Butler’s choices in framing, perspective, and lighting helped turn a troubled shark production into a masterpiece of suspense.

-

Jaws remains powerful because it doesn’t rely on CGI or constant monster reveals. Its restraint, combined with strong cinematography, natural performances, and John Williams’ unforgettable score, continues to scare audiences across generations

A personal ranking of the best horror movies of 2025, from experimental slow burns to grief-soaked nightmares that linger long after the credits.